Overview

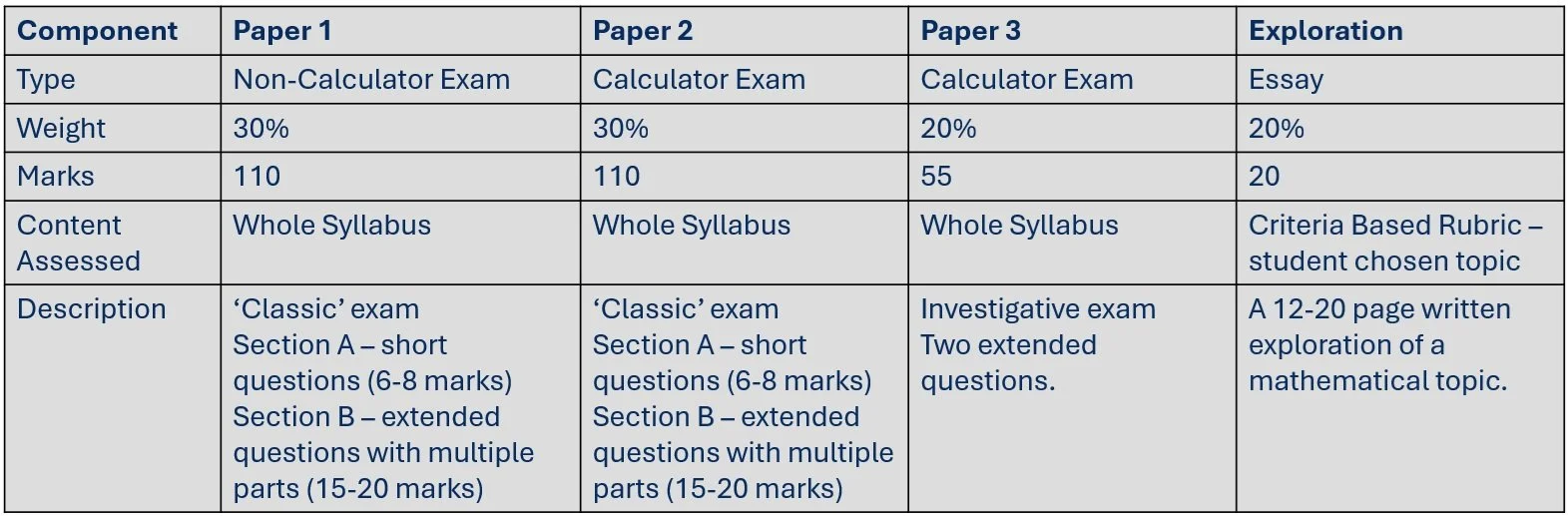

There are four components to the final grade that you are awarded:

Paper 1 - worth 30% of the final grade

Paper 2 - worth 30% of the final grade

Paper 3 - worth 20% of the final grade

Internal Assessment (The Exploration) - worth 20% of the final grade

Paper 1

Paper 1 is the only non-calculator component to the final assessment. There is usually a heavy reliance on Algebraic skills because of this. Whilst you are expected to have good basic numeracy, they are not testing this explicitly. You should be able to work with fractions confidently, but there should not be any overly complicated arithmetic that requires written methods.

The whole syllabus is examinable in this paper, but there are some topics that occur more frequently:

Logarithms

Complex Numbers

Sum and Products of Roots

Trigonometric Exact Values

Trigonometric Equations

Trigonometric Functions

Differentiating Polynomials

Differentiating Trigonometric Functions

Definite Integration

Discrete Random Variables

Vectors

There are also some topics that are VERY UNLIKELY to appear in Paper 1, due to reliance on the GDC:

Sequences and Series (can appear as a algebraic sequence)

Financial Maths (you are expected to use the GDC)

Permutations and Combinations (really big numbers usually that you are not expected to calculate by hand)

Statistics (mostly this is done with the GDC, though there are a few exceptions)

Binomial Distribution

Normal Distribution

Euler’s Method (you are expected to do this in the GDC)

The paper is split into two sections, with each section worth approximately half the total marks for the paper. All questions are ‘compulsory’ as in you do not choose between questions (though you might choose to not answer some as an exam technique to maximise marks).

Section A

Normally includes 9 questions, each worth 6-8 marks.

Many of these will be a single question, but some might include parts (a), (b) and (c). It is rare for there to be a part (d) in Section A.

The first 5 questions are common to the AASL paper, and so are usually a bit easier. You should be aiming to get all of these completely correct.

The final question of Section A is often the most difficult in the whole paper.

Section B

Normally includes 3 questions, each worth 15-20 marks.

Each question will include multiple parts and they build upon each part. Usually at least 5 parts, up to about 8 parts.

Common topics in Section B of Paper 1 are Complex Numbers and Vectors.

The first question in Section B is usually common to the AASL paper, and is often one of the easiest questions to get lots of marks quickly. I recommend doing this question first in an exam.

Paper 2

Paper 2 is the ‘main’ calculator component to the final assessment. There is usually a reliance on using the GDC efficiently in this paper to save time on arduous working. Look for equations that can be solved using the GDC quickly, including simultaneous equations.

The whole syllabus is examinable in this paper, but there are some topics that occur more frequently:

Sequences and Series

Permutations and Combinations

Sine and Cosine Rule, and Arcs and Sectors

Areas below curves (they are often looking for just the integral needed, and then for you to use the GDC to evaluate it)

Correlation and Regression

Conditional Probability

Binomial Distribution

Normal Distribution

Euler’s Method

Differential Equations

Whilst there are certain topics that are more likely to appear in Paper 1 due to the nature of the IB wanting to test them without a calculator, these topics can appear in Paper 2 as either ‘Show That’ questions (forcing you to show the algebra) or by using a twist (usually adding an unknown that makes using the GDC impossible).

The paper is split into two sections, with each section worth approximately half the total marks for the paper. All questions are ‘compulsory’ as in you do not choose between questions (though you might choose to not answer some as an exam technique to maximise marks).

Section A

Normally includes 9 questions, each worth 6-8 marks.

Many of these will be a single question, but some might include parts (a), (b) and (c). It is rare for there to be a part (d) in Section A.

The first 5 questions are common to the AASL paper, and so are usually a bit easier. You should be aiming to get all of these completely correct.

The final question of Section A is often the most difficult in the whole paper.

Section B

Normally includes 3 questions, each worth 15-20 marks.

Each question will include multiple parts and they build upon each part. Usually at least 5 parts, up to about 8 parts.

Common topics in Section B of Paper 2 are Statistics and Differential Equations.

The first question in Section B is usually common to the AASL paper (most likely Statistics), and is often one of the easiest questions to get lots of marks quickly. I recommend doing this question first in an exam.

Paper 3

Paper 3 is completely different in structure to Papers 1 and 2.

It consists of two long questions, each worth 25-30 marks, split into many parts. These often go up to a part (m).

Whilst the question does build up slowly, they are designed to have multiple ‘entry points’. This means, just because you cannot do part (a), doesn’t mean you can’t do part (c) and start from there.

Often an early part is a ‘Show that’ question, which means you can use this result, even if you were unable to do the algebra to show it to be true.

The nature of these questions in the AAHL course is usually of an investigative nature. Each question will either take an element from the syllabus and extend it in some way that takes you outside of the syllabus, or they will introduce you to a new topic of a similar difficulty and lead you through an investigation. In either case, unlike in Paper 1 and Paper 2, you will likely not have seen a question similar to these question before, though the mathematics you need to use throughout is based upon the syllabus content.

Differential equations is a very common topic to appear as one of the two questions in Paper 3.

Paper 3 is usually scheduled at least a week after Paper 2, which also gives you a chance to review the topics in Paper 1 and Paper 2, and look for those which have not yet been examined. It is likely these might form the basis of a Paper 3 question.

The Exploration

The Exploration is the internally assessed component of the AAHL course. All IB courses include a component which is not examined, and this is a form of coursework.

Logistically, what ‘internally assessed’ means is that it is marked by your teacher (or another teacher in the mathematics department at your school), and then a sample is sent to the IB for moderation. If there are 15 in your class, the IB will look at about 5 of these and determine whether the marks that your teacher has given those 5 pieces are well justified. If the IB agrees, the mark will remain. If the IB thinks your teacher was too harsh, marks will increase. If the IB thinks your teacher was too nice, the marks will decrease. Whatever decision is made, it is applied to ALL students in the class, not just the sample.

Realistically, you should expect some change in the mark that your teacher submits, and usually the IB makes some adjustment. For this reason, many teachers will not tell you the grade they submit, as it may change anyway.

The sample always includes the highest and lowest graded pieces in the class. In my experience, the IB never agrees with a full marks of 20, an so my personal approach is to be very strict when marking a piece that is very good. I rarely submit a piece with a mark higher than 18, as if I do and the IB disagrees, the marks of the whole class can be downgraded. Your teacher will have their own approach here, but this is worth bearing in mind if they tell you a grade they have submitted.

But what is The Exploration?

It is a 12-20 page written report of a mathematical exploration that you undertake. Broadly speaking these fall into a few categories:

Applying a topic from the course to some problem (e.g. statistical analysis, optimisation, volumes of revolution, setting up a differential equation, probability distributions)

Taking a topic from the course and extending it in some way (e.g. other types of financial mathematics, multi-variable functions)

Looking at a topic that is NOT in the AAHL syllabus, but is of a similar level of difficulty. This can be done by looking at topics in the AIHL course or A-Level syllabus that are not in the AAHL course (e.g. Voronoi Diagrams, numerical methods such as Trapezium Rule or Newton-Raphson, Graph Theory, Matrices, Hypothesis testing, Mechanics, Polar Coordinates, Hyperbolic Functions)

The Criteria are very clear: you do NOT need to choose a topic beyond the level of the course to achieve full marks.

In fact, choosing mathematics that is too difficult often leads to a poor exploration as you cannot demonstrate understanding.

What are the Criteria?

The Exploration is marked against 5 criteria. These are independent of each other, so you can score all the points in one criteria and none in another.

-

This criteria has nothing to do with the mathematical content of the exploration.

To get full marks it must be:

Coherent (logically developed with a good structure, easy to follow, and meets the aim)

Well-organised (includes an introduction and conclusion in the correct places, describes the aim clearly, has images/tables/graphs in sensible places)

Concise (does not show unnecessary or repetitive calculations or steps)

In summary, it is about how well structured the essay is. This has nothing to do with the mathematics explored.

-

This criteria assesses how relevant, appropriate and consistent the mathematical communication is.

Relevant - to the topic being explored

Appropriate - is it standard mathematical language/notation

Consistent - do you use it the same way throughout

This criteria looks at the notation you use, as well as the language. You must define any key terms not in the syllabus of the main course, and any variables you use (and use them consistently).

If appropriate, it is expected that you use different representations, such as graphs, tables, equations, formulae, diagrams, etc.

There can be NO examples of computer notation (e.g. x^2 instead of x²).

You should use the inbuilt equation editor in your word processor to style equations correctly.

Graphs must be labelled and use appropriate axes.

The mathematical communication that is appropriate will depend on the topic being explored, but not on the level or correctness of the mathematics.

-

This criteria is often misinterpreted in two ways. It is NOT:

about how much effort you put into the piece of work. Your teacher cannot just say that you worked hard to get a good mark.

about finding some flimsy way to justify your ‘innate’ interest in a topic. Nobody believes it when you say “I have always been interested in the shape of basketball shots”.

What is being assessed in this criteria is how much you engage with the exploration. Did you go beyond just a basic model, and try to improve it? Did you look beyond the most trivial examples and explore the boundaries of when it holds? Did you do more than the bare minimum to write 12 pages? Did you look at the topic from different or unique perspectives that are clearly your own?

Some topics lend themselves well to this, others less so. Choosing a ‘textbook’ style exploration might not do well in this criteria. Explaining an area of maths not in the syllabus but without your own application/interpretation will also not score well.

You need to ‘tell the story’ of how you explored the mathematics throughout the write up to show this. At each stage say something like “This made me wonder what would happen if…” or “I decided to see how this could be applied to…”. These statements show you are not just doing the basics, but exploring the topic in depth.

This is one of the hardest criteria to get full marks on.

-

Reflection is about thinking about what the mathematics you have explored tells you, and how you could improve or amend it in different scenarios.

At its most basic, it is stating what the results you have found tell you in the context of the exploration.

Critical Reflection means that these reflections change what you are doing in some way.

It is not just about saying some ‘standard’ limitations about what you have done (e.g. I could have collected more data, I haven’t taken air resistance into account). It is about meaningful reflections on what the mathematics tells you, and how this leads you to further explore.

In this way, it is linked to Personal Engagement.

In order to achieve the higher marks, the reflection should be throughout the exploration, and help develop the direction of the piece. If it is only included in the conclusion, it is unlikely to score well.

It is also very difficult to get full marks in this criteria.

-

This is the criteria where your actual mathematics is assessed. It needs to be:

Relevant - to the stated aim. Don’t include maths that is extra just to try to squeeze more maths in.

Commensurate with the level of the course - means that the level of difficulty is at the same level as the course being studied. It can be from the syllabus, or from similar level syllabi (such as A-Level or AIHL), but does NOT need to be more difficult. It can be SL content for this level.

Correct (or precise) - correct means there can be minor errors as long as they don’t detract from the work. Precise means there are no errors and suitable levels of precision are used.

Sophisticated - this is where HL content is useful. If you do SL content, it is hard to get this level (though that might be a sacrifice worth making).

Rigorous - deductive and logical arguments are used, including proofs or at least justifications.

Thoroughly understood (demonstrated) - this is really important. You MUST demonstrate your understanding if the mathematics. This includes explanations, examples and diagrams (if appropriate) to show that you understand, and are not just following some routine procedure.

It is better to do a small amount of mathematics really well, than to do lots of mathematics (that is not relevant) and not show you understand it.

Often students either try to include mathematics that is far too difficult (University level) which they cannot demonstrate understanding of, or they include too many different bits of maths which are not all relevant (and this usually makes it less coherent too).

Focus on the mathematics relevant to your topic, and show you understand it.

Is it sensible to ‘sacrifice’ a criteria?

In short, usually yes.

It is almost impossible to get the full 20 marks, and even a score of 19 is rare. The average mark is a 12-13, so you are looking to maximise the marks in some criteria.

For example, whilst a volumes of revolution question might not lend itself well to scoring well in Personal Engagement, it is well suited to all the other criteria and fairly easy to understand. This means it could score top marks in four criteria, giving a total of 18.

Similarly, if you are aiming for a grade 4, then you are probably better choosing a mathematical topic from the SL course. Whilst this might limit you to 4 out of 6 in Use of Mathematics, you have a better chance of demonstrating understanding, being coherent and using appropriate mathematical communication in order to maximise points.